Sun Ra

Baked

- User ID

- 2854

Some John Birmingham for your Saturday arvo ......

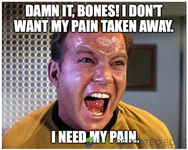

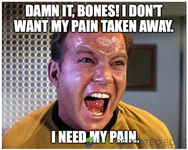

Leave me with my pain.

May 24

Stricken this week with Man-Flu, I took to my deathbed with Lemsip and iPad, bravely awaiting The End. While dying*, I watched Her, Spike Jonze’s 2013 romantic tragedy in which Joaquin Phoenix falls in love with Siri, as voiced by Scarlett Johansson. I imagined that since I would soon be dead anyway, it would be nice to distract myself with a robot uprising story in which the robots rise up and kill everybody.

That’s my favourite sort, and honestly, that’s what I thought I was getting, but that’s not what happened. Instead, I watched a very sad love story by accident, and it made me so sad my Man-Flu died before it could kill me. So that was good, I guess.

Of course, the other reason I watched it was Scarlett Johansson calling out maximum AI danger boy Sam Altman for stealing her voice and giving it to his new AI lovebot, ‘Sky,’ on ChatGPT this week.

As someone whose books were stolen to feed the Large Language Model embiggening Sam Altman’s personal worth, I had some sympathy for Ms Johansson.

Also, as someone with a limited set of skills, all of them dependent on juggling words into pleasing arrangements, I foresee a day that Sam Altman gets paid for Chat-GPT auto-generating a new John Birmingham book, and I get to sleep under a bridge.

Perhaps Scarlett and I could warm our hands together over the oil drum fire down there. That would be nice.

The Johansson thing, as Charlie Warzel points out in The Atlantic, is merely a reminder of Big Tech’s AI manifest-destiny kink: This is happening, whether you like it or not. “When your technology aims to rewrite the rules of society, it stands that society’s current rules need not apply.”

I suspect it’s why so many of my writer friends have an almost jihadist fear and loathing of Artificial Intelligence. It seems purpose-built to make us redundant at best or to exterminate us in the worst of cases. At least in the latter extreme, our misery would have company. You would all be fed into the shredders along with us.

This is the Terminator vision of AI gone wrong, and although it plugs directly into the more personal and intimate fears of those with greater exposure to Altman’s manifest destiny, I don’t think it’s the most likely existential downside.

I think the proximate danger is more Star Trek than Terminator. There is a meta-narrative of pain running from Kirk through Picard to whoever is serving as le capitaine-du-jour these days: the idea that pain and suffering are defining qualities of the human experience.

But the defining quality of the digital age is the algorithmic elimination of any pain and all suffering, no matter how liminal. “There’s an app for that,” promises a balm of code for any discomfort, from the pain of actually talking to another human being to order delivery noodles to the anguish of talking to another human being to decide whether they might be interested in dating you.

Indeed, “talking to another human being” is the behaviour most devalued and succeeded by AI’s threatening promise, especially as it slouches towards sentience—or some rough approximation thereof.

I don’t see the threat of AI as coming from a handful of billionaires who want to be trillionaires inventing a robo-writer that can churn out better airport novels than me in less time than it takes me to reach down and pull out its power chord.

My fear is that in our collective desire to avoid the friction and pain of being human, we’ll outsource to the machines so much of what gives rise to that friction and pain that what’s left is a very poor, undeveloped simulacrum of humanity and that such poverty of being and meanness of spirit could easily become the baseline.

The internet did not destroy our attention spans. Algorithms designed to attack the dopaminergic response chain and deliver billions of eyeballs to advertisers on sites and services like Facebook and TikTok destroyed them. You can read every volume of Gibbons’ Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire online if you want. But you’re more likely to click on a video of a cat riding a Roomba, and then another cat riding a different Roomba, and then something about Nazis. None of which was AI-driven.

But soon enough, everything will be.

And sure, it will suck when the skies fill up with AI-powered drones dropping grenades on us, but I suspect we’ll have screwed ourselves long before then by ceding to the machines, so much of what made us human in the first place.

* I got better.

Leave me with my pain.

May 24

Stricken this week with Man-Flu, I took to my deathbed with Lemsip and iPad, bravely awaiting The End. While dying*, I watched Her, Spike Jonze’s 2013 romantic tragedy in which Joaquin Phoenix falls in love with Siri, as voiced by Scarlett Johansson. I imagined that since I would soon be dead anyway, it would be nice to distract myself with a robot uprising story in which the robots rise up and kill everybody.

That’s my favourite sort, and honestly, that’s what I thought I was getting, but that’s not what happened. Instead, I watched a very sad love story by accident, and it made me so sad my Man-Flu died before it could kill me. So that was good, I guess.

Of course, the other reason I watched it was Scarlett Johansson calling out maximum AI danger boy Sam Altman for stealing her voice and giving it to his new AI lovebot, ‘Sky,’ on ChatGPT this week.

As someone whose books were stolen to feed the Large Language Model embiggening Sam Altman’s personal worth, I had some sympathy for Ms Johansson.

Also, as someone with a limited set of skills, all of them dependent on juggling words into pleasing arrangements, I foresee a day that Sam Altman gets paid for Chat-GPT auto-generating a new John Birmingham book, and I get to sleep under a bridge.

Perhaps Scarlett and I could warm our hands together over the oil drum fire down there. That would be nice.

The Johansson thing, as Charlie Warzel points out in The Atlantic, is merely a reminder of Big Tech’s AI manifest-destiny kink: This is happening, whether you like it or not. “When your technology aims to rewrite the rules of society, it stands that society’s current rules need not apply.”

I suspect it’s why so many of my writer friends have an almost jihadist fear and loathing of Artificial Intelligence. It seems purpose-built to make us redundant at best or to exterminate us in the worst of cases. At least in the latter extreme, our misery would have company. You would all be fed into the shredders along with us.

This is the Terminator vision of AI gone wrong, and although it plugs directly into the more personal and intimate fears of those with greater exposure to Altman’s manifest destiny, I don’t think it’s the most likely existential downside.

I think the proximate danger is more Star Trek than Terminator. There is a meta-narrative of pain running from Kirk through Picard to whoever is serving as le capitaine-du-jour these days: the idea that pain and suffering are defining qualities of the human experience.

But the defining quality of the digital age is the algorithmic elimination of any pain and all suffering, no matter how liminal. “There’s an app for that,” promises a balm of code for any discomfort, from the pain of actually talking to another human being to order delivery noodles to the anguish of talking to another human being to decide whether they might be interested in dating you.

Indeed, “talking to another human being” is the behaviour most devalued and succeeded by AI’s threatening promise, especially as it slouches towards sentience—or some rough approximation thereof.

I don’t see the threat of AI as coming from a handful of billionaires who want to be trillionaires inventing a robo-writer that can churn out better airport novels than me in less time than it takes me to reach down and pull out its power chord.

My fear is that in our collective desire to avoid the friction and pain of being human, we’ll outsource to the machines so much of what gives rise to that friction and pain that what’s left is a very poor, undeveloped simulacrum of humanity and that such poverty of being and meanness of spirit could easily become the baseline.

The internet did not destroy our attention spans. Algorithms designed to attack the dopaminergic response chain and deliver billions of eyeballs to advertisers on sites and services like Facebook and TikTok destroyed them. You can read every volume of Gibbons’ Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire online if you want. But you’re more likely to click on a video of a cat riding a Roomba, and then another cat riding a different Roomba, and then something about Nazis. None of which was AI-driven.

But soon enough, everything will be.

And sure, it will suck when the skies fill up with AI-powered drones dropping grenades on us, but I suspect we’ll have screwed ourselves long before then by ceding to the machines, so much of what made us human in the first place.

* I got better.